The Openmusic Project

Let's shine a light

The problem with the music industry is one of economic and technological dysfunction. There is no single solution. But if we want more, better music – not just for ourselves but for future generations – then systemic change is necessary.

Ideas are helpful, but we learn more by building. So we start with a prototype for the Openmusic project, not to be confused with the excellent Open Music Initiative at the Berklee College of Music, which focuses primarily on metadata.

What follows is a brief narrative describing how we got to this point and a rough sketch of the project.

The magical sprite

Channelling Arthur C. Clarke's theory that "any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic", we propose giving each and every musician their own magical sprite.

As a music creator, when you compose and record new music, the sprite gets to work connecting you with collective rights organizations, radio stations, distributors, and audiences. It takes care of your administration, billing, payments, and settlement. It's there to help you gather and control all the metadata associated with your music, connect you with fans, and introduce you to other like-minded, talented people you might want to collaborate with.

The sprite, of course, is software – computer code written with a generous spirit and a moral compass. With help from your sprite, you should have a better chance of putting bread on your table and paying your bills. And while the analogy is magical, the software tools required to build a new operating system for the music industry are not: they are real and at hand.

The think-tank Water & Music has suggested that "[a] large part of the utopian narrative around how blockchain technology will impact the music industry revolves around perpetual, platform-agnostic, trustless and automated payments to multiple owners". They are not wrong, but it's not the whole story. Multiple software tools are needed. Some, like blockchain, are caught up in the techno-utopian zeitgeist of the moment; others – programming languages and frameworks and open-source patterns and so on – might not be cultural memes, but they have value nonetheless. What they all have in common is the conscience of a steel ball. What matters is how we use them and for what purpose.

The cartel

In the early 2000s, illegal file sharing over peer-to-peer networks rocked the music industry to its core. In his commentary, Awakening the Music Industry in the Digital Age, Mark Mulligan, head of Midia Research, recalls a record label meeting with senior executives who were shown Napster for the first time. Their reaction was fear. Or, as one attendee put it: "We're so fucked. Who can we sue?"

Litigation became part of a retrograde attempt to regain market power. The more effective strategy, which shifted the industry's tectonic plates and created the oligopoly we see today, involved a series of mergers and acquisitions and private equity investments.

By 2013, the music marketplace was dominated by three multinational firms: Universal, Sony, and Warner. Previously, in the summer of 2012, Edgar Bronfman Jr., head of Warner Music, gave evidence at a United States Senate antitrust hearing opposing Universal's acquisition of EMI Group, which was the fourth-largest record label in the world at the time. In summary, Bronfman said:

"... the EMI/Universal merger would do pervasive and permanent damage to digital innovation, to the music industry, and to the American consumer... [It] would mean a world where one dominant company—Universal/EMI—sets the prices, terms and conditions for future digital evolution. Where that company would stand as gatekeeper between consumers and choice, and where digital innovation, one of the main engines of economic growth in this country, would be stifled solely for the benefit of one already large company that wants to become one dominant giant."

The merger was allowed. According to Nielson SoundScan, it enabled control over a combined market share of 88.5%. Billboard magazine later reported that more than half of the eight-member subcommittee deciding the merger's fate took campaign donations from the two music industry giants: Universal and EMI.

Issues not addressed at the Senate hearing included the level of control over distribution that the major labels were already exercising through their combined shareholdings in Spotify and the fact that Sony's distribution agreement with Spotify, signed 18 months before the hearing (and subsequently leaked), contained a lengthy most favoured nation (MFN) clause. Many have argued, including the American Bar Association, that "MFN clauses ... can be used to facilitate collusion amongst competitors ...". Essentially, they allow suppliers to signal their preferred contractual terms to would-be competitors, so they might, as a group, apply terms that are the same or similar. It avoids competition. The fewer suppliers, the more powerful the ploy.

According to Maria Eriksson at Umeå University in Sweden and the research team behind Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music, "... the so-called Big Three ... form an oligopoly that can act as a cartel when dealing with any music streaming service. Importantly, Spotify and its competitors depend on the same product: a distribution license for what consumers accept to be all music".

Testimony at the British government's recent inquiry into the economics of streaming supports Eriksson's findings. For example, the de facto royalty share model instituted by the major labels reflects asymmetric bargaining powers, if not outright collusion. As Mark Mulligan stated: "The net effect is that each major [label] has the equivalent power of a UN Security Council veto. Few music services have had success launching without all three major labels licensed".

The British inquiry has shed light on how Spotify's capitalization model disadvantages creators and how systemic controls written into industry contracts and agreements ensure diminishing returns for the creator community. Session players, for example, receive a small royalty every time their music is played on the radio. But they receive nothing when their music is streamed: an industry practice that contravenes the spirit and, arguably, the terms of the Treaty of Rome.

The major labels are global conglomerates with interests in multiple recording and publishing companies. Their ownership and control over the copyrights required to stream music allow them leverage and influence in any agreement where the third party is a distributor. The British government's report on streaming concluded: "As long as the major record labels also dominate the market for song rights through their publishing operations, it is hard to see whether the song will be valued fairly as a result".

Consolidation of power

Consolidation of power in the music industry begs the question: so what? Audiences never had it so good. A global and historical wealth of music is available from streaming services at a small, sometimes zero cost to consumers.

Alas, not everyone can make it in the music business. Talent is, and always has been, unevenly distributed. (My sense of rhythm would embarrass a squid in electroshock therapy.) Perhaps that's why, according to Spotify, only 0.2% of artists earn more than $50,000 per year from its platform.

In a 2020 interview for the online music journal Music Ally, Daniel Ek, Spotify's multi-billionaire CEO, said:

"The artists today that are making it realize that it's about creating a continuous engagement with their fans. It is about putting the work in, about the storytelling around the album, and about keeping a continuous dialogue with your fans."

The musicians I have met are no strangers to hard work. Maybe unsolicited advice and condescension from fat cats goes with the territory.

Ek has a talent for eliding two facts. Firstly, Spotify's main function is to serve as a gatekeeper and cash delivery mechanism for an oligopoly, where the prime directive is to perpetuate terms of agreement with artists formulated in the non-digital era. Secondly, Spotify's early success in Sweden was built on the back of unlicensed, pirated music. Judging by the recent flow of copyright infringement lawsuits, the thievery continues.

Spotify's M.O. has been to sustain continuous losses to support the expansion of its user base. The upside for senior management and investors is measured not in profits but in capital gains, which are not shared with music creators but are eligible for favourable tax treatments. The strategy works well if you want to shove competitors to the sidelines and attain 800-pound gorilla market power. The company's record of marginal profitability might also help keep regulators, for whom the model is new and unfamiliar, onside.

Undoubtedly, theories and principles of distributive justice are a miasma of economic debate and ideological cant. What are clear and measurable, however, are the increasing revenues and fatter margins in digital music markets resulting from lower production, manufacturing, storage, packaging, and distribution costs. Those gains are not accruing to music creators.

In 2021, Universal Music Group chairman and CEO Lucian Grainge received total compensation of $303.6 million. Depending on your point of view, the payout was either well-deserved or obscene, or perhaps a mixture of both. More to the point is the plutocratic nature of corporate control that monopolizes the work of generations of artists to maximize financial rewards for a select few.

Britain's Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has noted:

“The majors have significant advantages linked to their scale that are difficult for independent record companies [and artists] to replicate. Most notably the majors’ ownership and earnings of large back catalogues of music for which they have long-term rights gives the majors significant financial advantages. Back catalogues are responsible for over 80% (in 2021) of music streams and therefore account for a high proportion of streaming revenues.”

Scale enables the major labels to dictate contractual terms and de facto rules. For example, independent musicians cannot upload their work directly to the big streaming companies, they must pay to use an intermediary service such as DistroKid or Landr or Tunecore. Session players are disenfranchised. Their work is played, but they get no money from it; their legally defined "neighbouring rights" are not recognized. And then there is payola. Payola is a bribe paid to a radio station or disc jockey to promote a particular song. For terrestial radio, it is illegal, but not for digital streaming companies. Spotify calls it Discovery Mode. Which is another way of saying you can pay to have your song promoted in a playlist.

Spotify pays on average about $0.004 per play, so a million streams will earn around $4,000. If you have a label deal or your band includes several members, that amount will need to be shared. Sign up for Discovery Mode and the amount will be less.

Many have spoken out against corruption in the music industry. Tom Gray's #BrokenRecord campaign is one of several grass-roots movements working to inform the public and ignite change. A-list artists are also confronting the problem. When Universal Music Group sold shares in Spotify a few years ago, Taylor Swift demanded that some of the proceeds be paid to herself and other signed artists. Universal agreed. Perhaps to deflect attention from their original agreement with Spotify, which included generous advance payments to the company but cut artists out of the deal.

Yet neither agitation for economic justice nor the occasional concession from a major label will likely make a difference. Political actors – bought and paid for by corporate interests or ideologically predisposed to trickle-down economics – will continue to support inertia. Reports from the British inquiry into the economics of streaming, for example, have been punted from one government department to another. Following the inquiry, the CMA gave a broad exemption to the big three labels and their associated streaming services. Recognizing that "overall, consumer satisfaction with music streaming services is high”, they decided not to pursue the matter.

Meanwhile, the economic incentives for anyone considering music as a choice of study or career are diminished.

Copyrights / Copywrongs

Copyright is the legal mechanism that awards exclusive time-limited rights to creators to encourage production and public access to cultural works. It embodies a utilitarian ethic that balances private and public interests. From it, we get the notion that cultural production can be engineered.

Ironically, the first copyright statute, the Statute of Anne, was designed to end a monopoly held by the Stationers' Company, a printers' guild, over what could be published. The statute meant that, for the first time, ownership rights could be vested in authors. It included provisions for the public interest, such as a legal deposit scheme, a forerunner of the modern library; it curtailed censorship and promoted commerce and innovation. The original term of copyright was fourteen years.

Music copyright inherited its DNA from the Statute of Anne and other sources. Its control surface includes several legal and socio-political mechanisms: jurisprudence, legal precedent, academic work, government-appointed bodies, such as copyright royalty boards which adjudicate statutory licensing rates, and so on. In recent decades, three (and possibly more) extrinsic factors have altered that control surface. They include peer-to-peer networks that distribute unlicensed music, safe harbour laws that protect large corporations from copyright infringement liability, and music industry consolidation.

Consolidation is implicated because it has enabled the major labels to secure preferential and homogeneous licensing agreements with a small group of streaming services: Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, Tencent, Google, and a few others. Collectively, they operate as a privatized global utility delivering tens of millions of songs to hundreds of millions of people. It is a system of interdependencies designed to appropriate value from goods produced by others through the application of monopoly power. When that power is exercised, commercial incentives for music creators are eroded and the capability to originate new music is compromised. Arguably, it is a state of play that runs contrary to copyright's original intent and ethos.

To be fair, the big tech streaming companies allow almost anyone to upload their tracks. Which is, perhaps, a good thing. Aside from having to pay access fees to intermediaries, the barriers to entry are remarkably low: tens of thousands of tracks are uploaded every day. Volume, however, is not an indication of the value on offer. It's more likely to be a signal that competition is lacking.

The mission

The mission is to build a system that rewards music creators fairly and equitably for their work.

There are at least three evolving and inter-related models:

1. An authentic and (almost) frictionless economic alignment among creators and audiences;

2. An algorithmic licensing, collections, payment and settlement layer that is secure, fair and transparent; and

3. A capital markets model that funds new music development, production, and marketing in exchange for a share of future royalties and other rewards.

Antecedents for the capital markets model date back to the securitization of David Bowie's royalties in the 1990s. While firms such as Hipgnosis have focused on acquiring back catalogues, the emerging opportunity is to fund the creation and delivery of new music. Several tools are available, including microfinance, fractional NFTs (non-fungible digital tokens), and decentralized exchanges (peer-to-peer marketplaces dedicated to trading and investing in music royalties).

The prototype

The Openmusic prototype does two things: it algorithmically matches musicians' talents and interests to new projects, and it establishes simple processes for developing and managing those projects. As a musician, it means you can find your people – people who inspire and challenge you and can help create new sounds. And it means you can speed up your workflow.

As we build out the platform to include new services, there are several core problems to address as well as some guiding principles. They include:

1. Mitigate creators' transaction costs. Transaction costs (which involve the loss of time and money) are to economics what friction is to engineering. The idea is to mitigate those costs for music creators.

2. Creators retain full ownership and control of copyrights. There are two copyrights in any musical work: one in the composition and another in the sound recording. Our task is to help owners capture and control their rights at the earliest stages of music development.

3. Privacy. There are no plans to harvest and sell user data or impede workflow with sponsored messages.

4. Decentralization. Software is brittle and subject to multiple points of vulnerability, so we build protections based on decentralization and modular development practices. For example, the prototype uses the Dropbox API (application programming interface) for file sharing, permissions, and security. It enables musicians to access their work, even if the system fails. Future iterations could use a peer-to-peer network to achieve similar aims.

5. Human-focused design. A good tool should be an extension of human reach and control. It should feel right. It should ease the burden of the work and be a pleasure to use.

More about transaction costs

According to economist Ronald Coase, the level of efficiency in an organizational structure is determined by its transaction costs (costs of exchange). An organization can be more or less self-contained, as in a modern corporation with many employees, or open, as in the case of independent musicians who coordinate several external factors of production and distribution to exploit their work.

Research at Berklee ICE, part of the Berklee College of Music, has found that musicians who follow the standard practice of outsourcing their transactions (i.e. selling and licensing their copyrights via record labels, publishers, distributors, and others) operate in an opaque marketplace that limits their earning power. The authors conclude that "[the] current lack of transparency appears to benefit middlemen, but creators, consumers, and others in the music industry value chain should no longer passively accept this".

More about decentralization

Decentralization is an ongoing topic of conversation among software developers. For example, Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin concluded that "there are actually three separate axes of centralization/decentralization: [architectural, logical and political] ... One simple heuristic [for logical decentralization] is: if you cut the system in half, including both providers and users, will both halves continue to fully operate as independent units?".

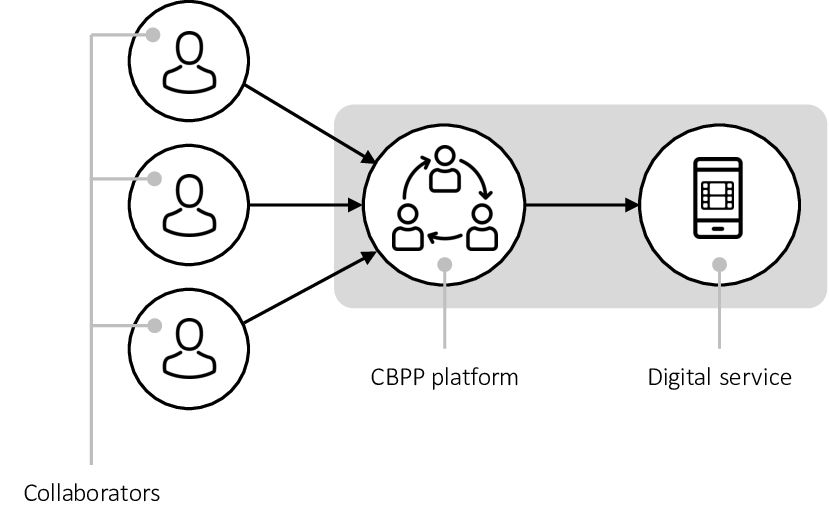

For the Openmusic project, logical decentralization offers greater security and resilience for users. Political decentralization provides a pathway to democratic governance. Moreover, a decentralized network is an appropriate structure for self-organizing processes such as commons-based peer production (CBPP). CBPP can be found in various applications, including Wikipedia and GitHub, a digital platform that helps software engineers discover, contribute to, and organize open-source projects.

The gift

In the nature of music and how it's created, we recognize a duality: it is both a product and a gift. Many of us start playing and performing after receiving a musical instrument from a family member or a friend. The prototype is a gift in that tradition. The idea is to help musicians create and manage their projects within a safe, hassle-free environment. As we extend the platform, the service will include handheld applications, music discovery, fan engagement, and more.

What's next?

With the rise of monopolistic corporate power and the weakening of antitrust regulations, we find ourselves on a path towards greater commodification of music, a political economy that encourages capture and profit from the social value of musical works, and a market in which cost and risk are increasingly the burdens of music creators.

In their recent research report, Goldman Sachs estimates the music market will be worth US$153 bn in 2030. Record labels have improved their profit margins in the transition from physical to digital formats. Those margins are typically associated with back catalogues, so they are trying to figure out how to acquire new content at lower costs.

On the other side of the digital fence is a global community of musicians looking for a fair deal – and, maybe, a revolution.

Let's make it happen.

Note: I live just outside Toronto, Canada. If you are a software engineer, musician, or investor, reach out! I would love to meet up for coffee and a conversation. A Google Meet or a phone call would also be great. You can reach me at: david@openmusic.io.